Tracing Time: A Process in Layers

The endless stacks of photographs I collected from my grandfather came to me mostly unmarked and without order — over 5,000 images stretching seven decades for four generations. I spent nearly a year arranging the archive by time, not just to organize chronologically, but to understand. Time became both structure and subject, a way of sensing the collection and making sense of the lives held within it.

As I moved through the images, box by box, I tried to place the years. Most were taken long before I was born, but I had a desire to understand the history I came from, not just for myself, but for the generations who will one day have questions of their own. I wanted the archive to be more than just images. I wanted it to carry context and continuity with a sense of structure.

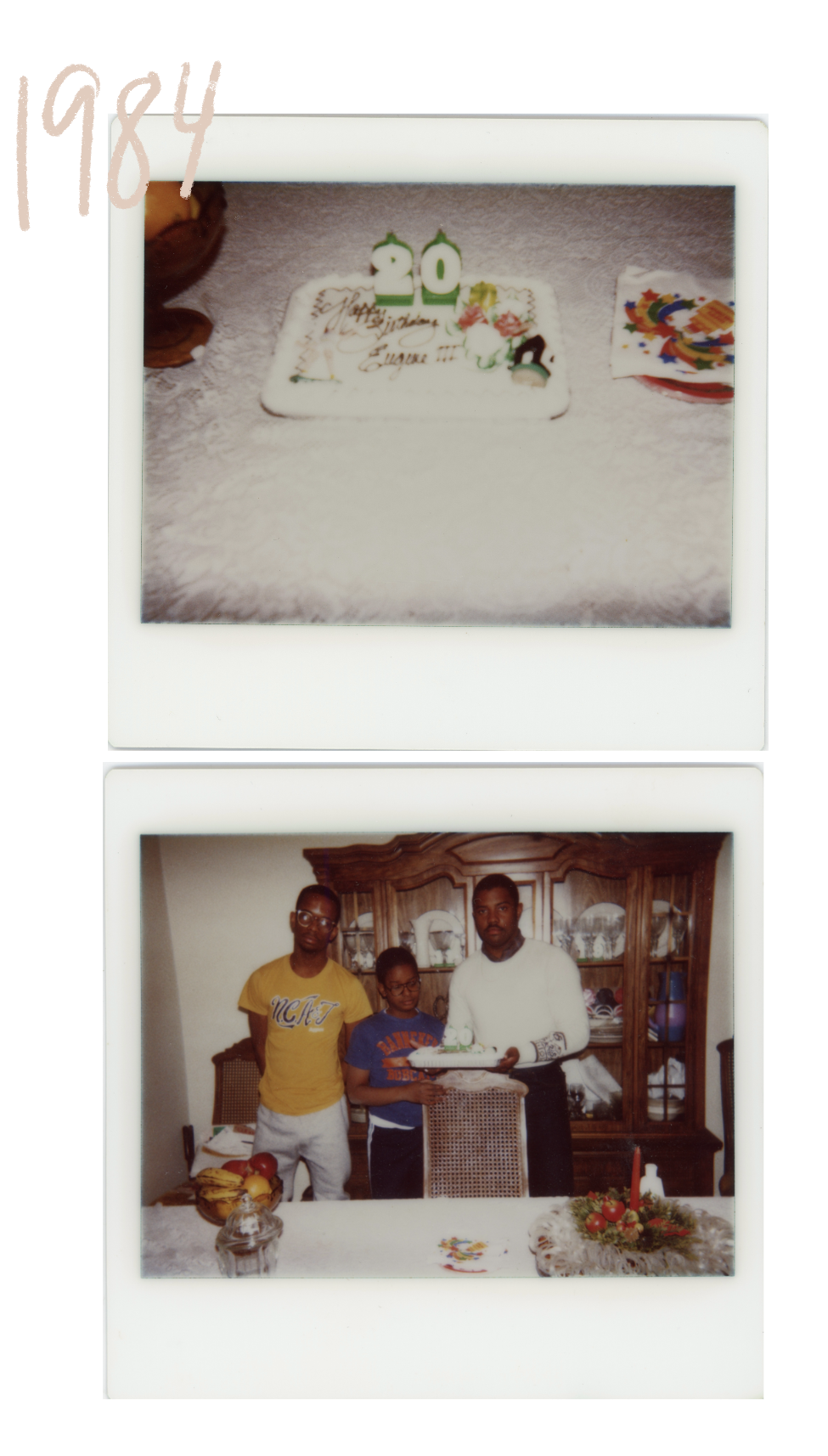

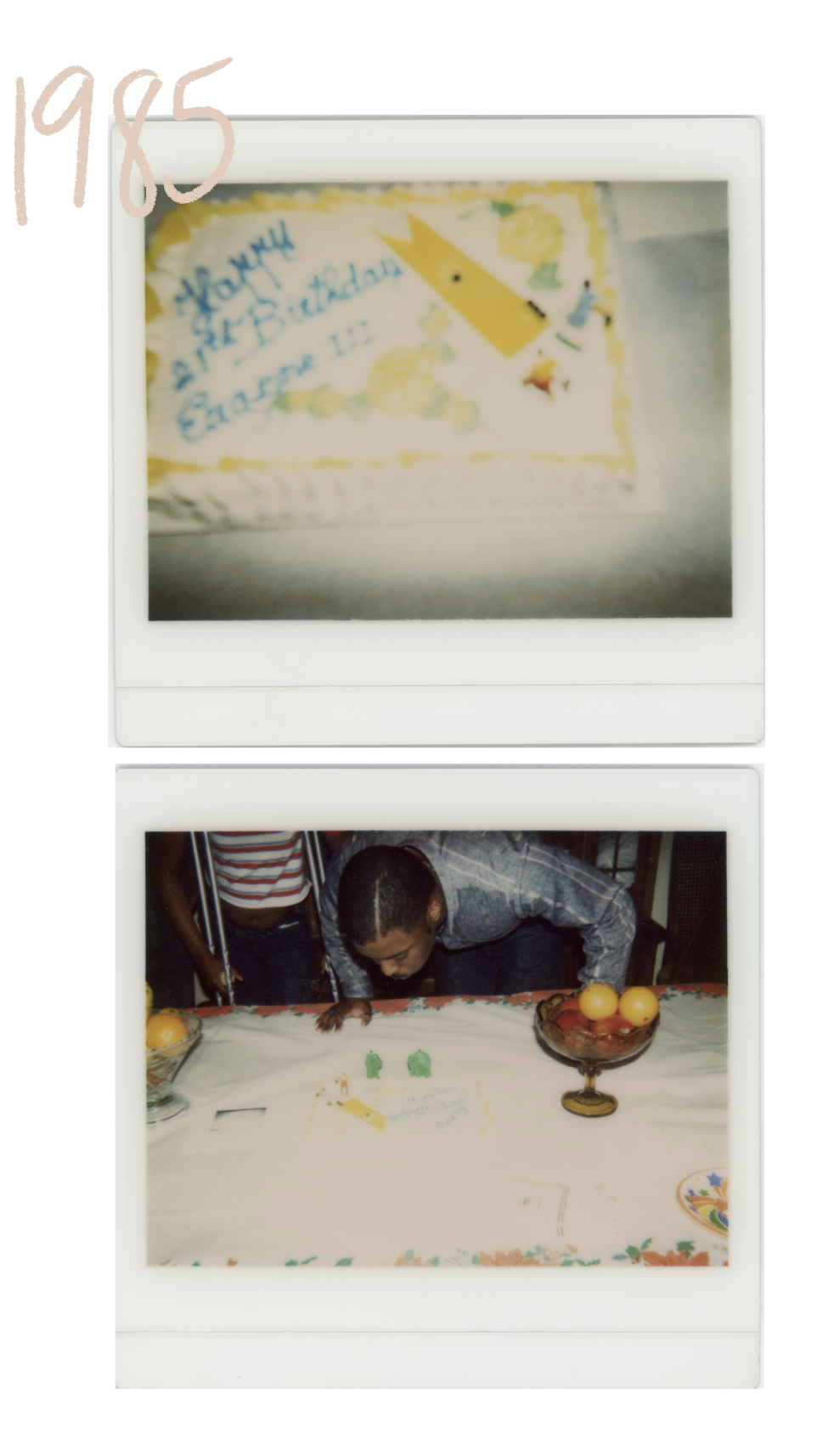

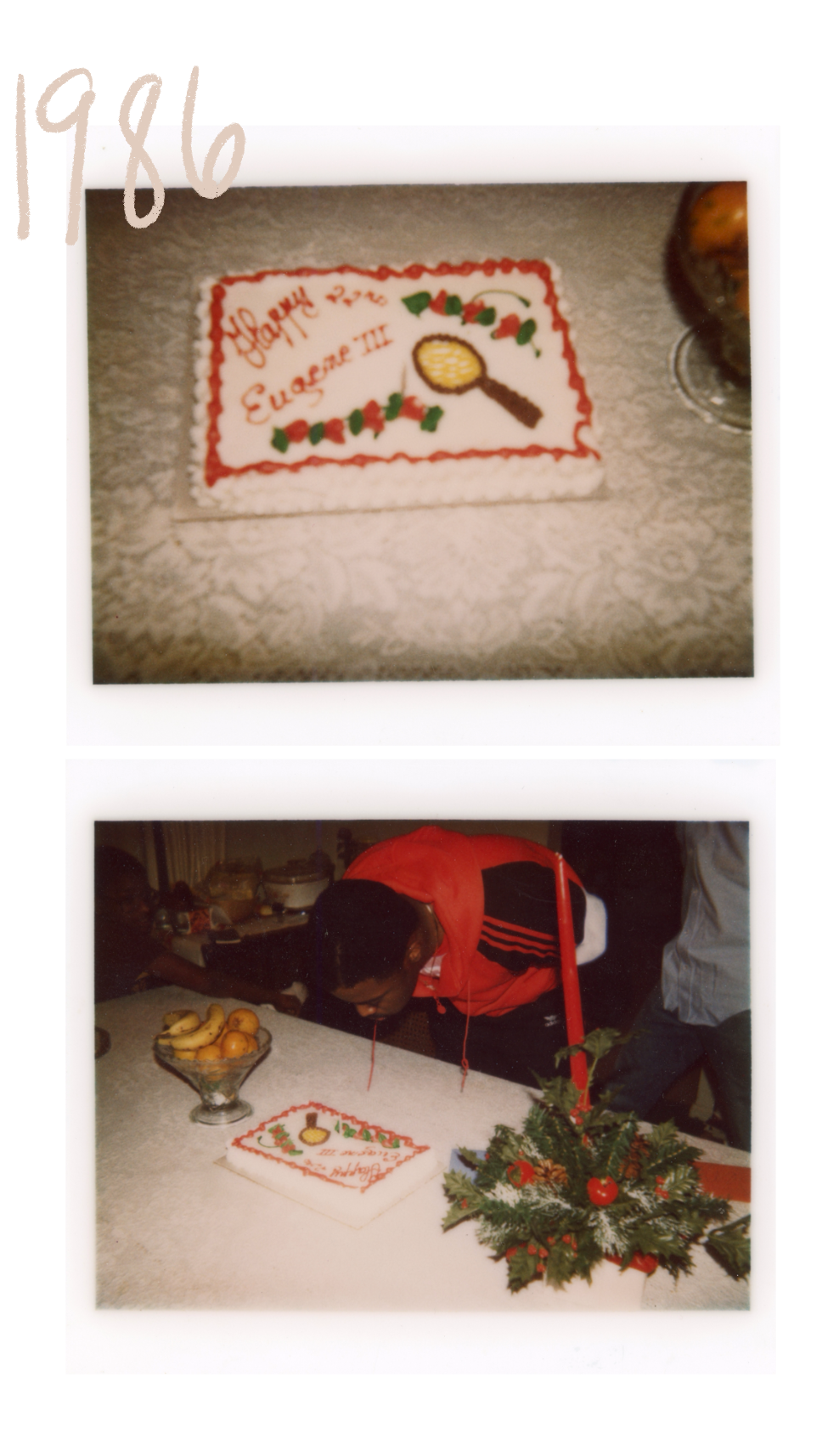

I kept returning to the same question: When were these taken? Some clues were material—developer stamps, lab markings, or handwritten notes pressed into the backs of prints. Most of the dates were absent and unclear. I learned to read more subtle cues: shifts in fashion, aging faces, the number of candles on a birthday cake.

I began to understand that tracing time in photographs isn’t about precision. It’s about perception. It’s a layered process—part tactile, part intuitive—that reveals not just when a photograph was made, but what dimensions of time it holds. Time is traceable in photographs, even when it’s not labeled. You just have to pull back the layers to begin to see it.

Physical time is the most visible dimension of a photograph, leaving marks we can see and measure. The wear of time reveals itself through browning paper, creases, and fading ink. Textural clues like glossy finishes, scalloped edges, or sepia tones suggest a particular era. These signs act as visual timestamps, revealing when a photograph might have been taken or how long it’s been held, stored, or left untouched.

Physical time isn’t only embedded in the print; it also reveals itself in the people. Aging shows up in subtle ways: the softening of a jawline, the deepening of smile lines, the presence—or absence—of gray at the temples. A photograph holds both the aging of its surface and the aging of its subjects.

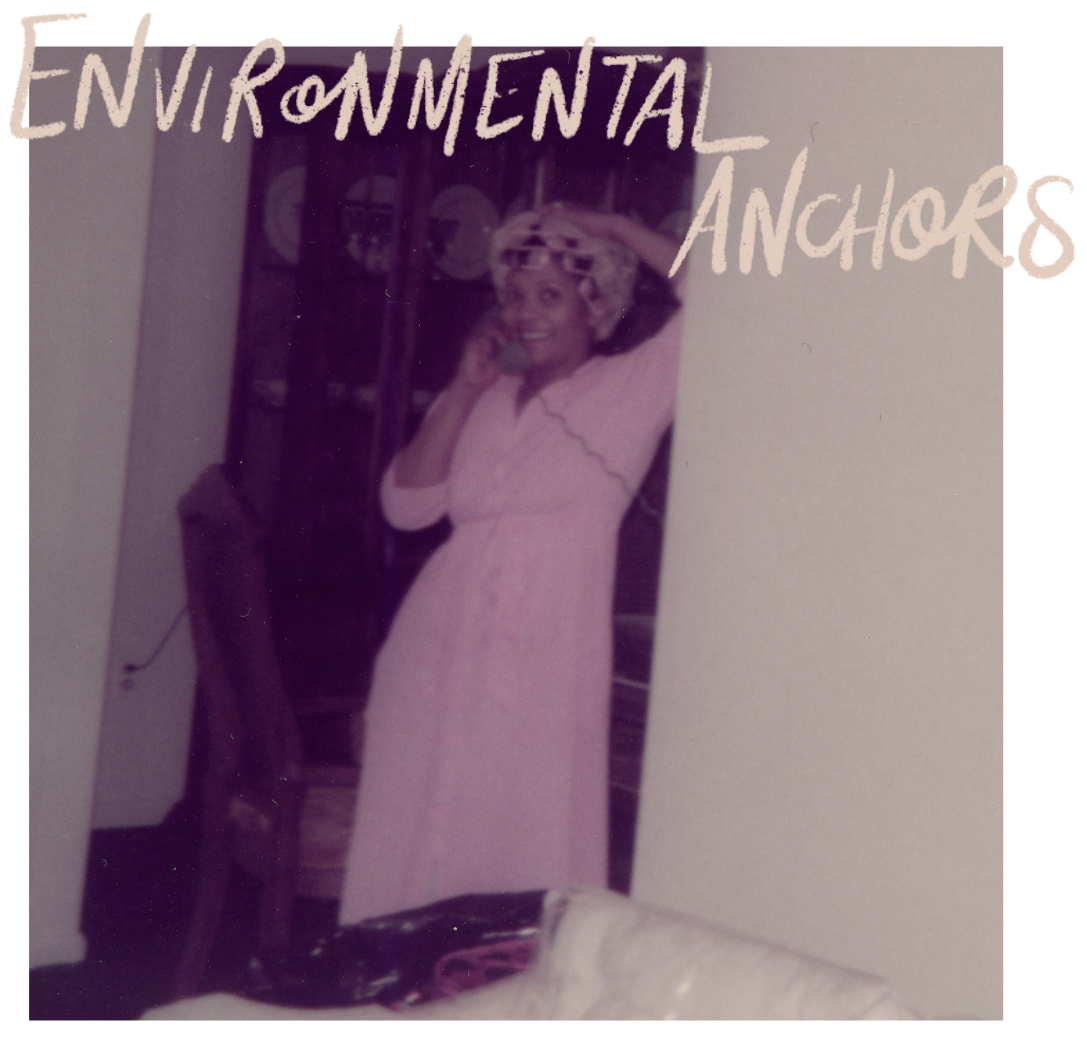

The atmosphere carries history in plain sight, if you know where to look. It appears in the ordinary things that subtly mark an era: the plastic on the sofa, a landline telephone cradled on a shoulder, or tinseled holiday decorations not only date the photo — they’re visual anchors that reveal the temporal setting. When observed together, they begin to triangulate a moment in time.

Holidays and family traditions offer even more cues: a tree draped in tinsel, a birthday cake with numbered candles, a themed tablecloth. These recurring rituals carry slight variations—subtle shifts in who’s present, who’s old enough to decorate, who’s moved away that help distinguish one year from the next. Time reveals itself not just in what is happening, but in who is changing.

When reading photographs for context, it isn’t always explicitly stated what’s happening in a photo, sometimes it lives in the margins. This is where the art of noticing takes shape: in paying attention to the language of the background and particular circumstances.

In one stretch of photos from the late ’80s, my uncle appears repeatedly on crutches. At first glance, it seemed like a passing detail, but eventually it marked a clear moment in our family’s timeline. Context lives in repetition, in circumstance, in the fragments that might seem incidental but shape how we place an image within memory.

circa 1992

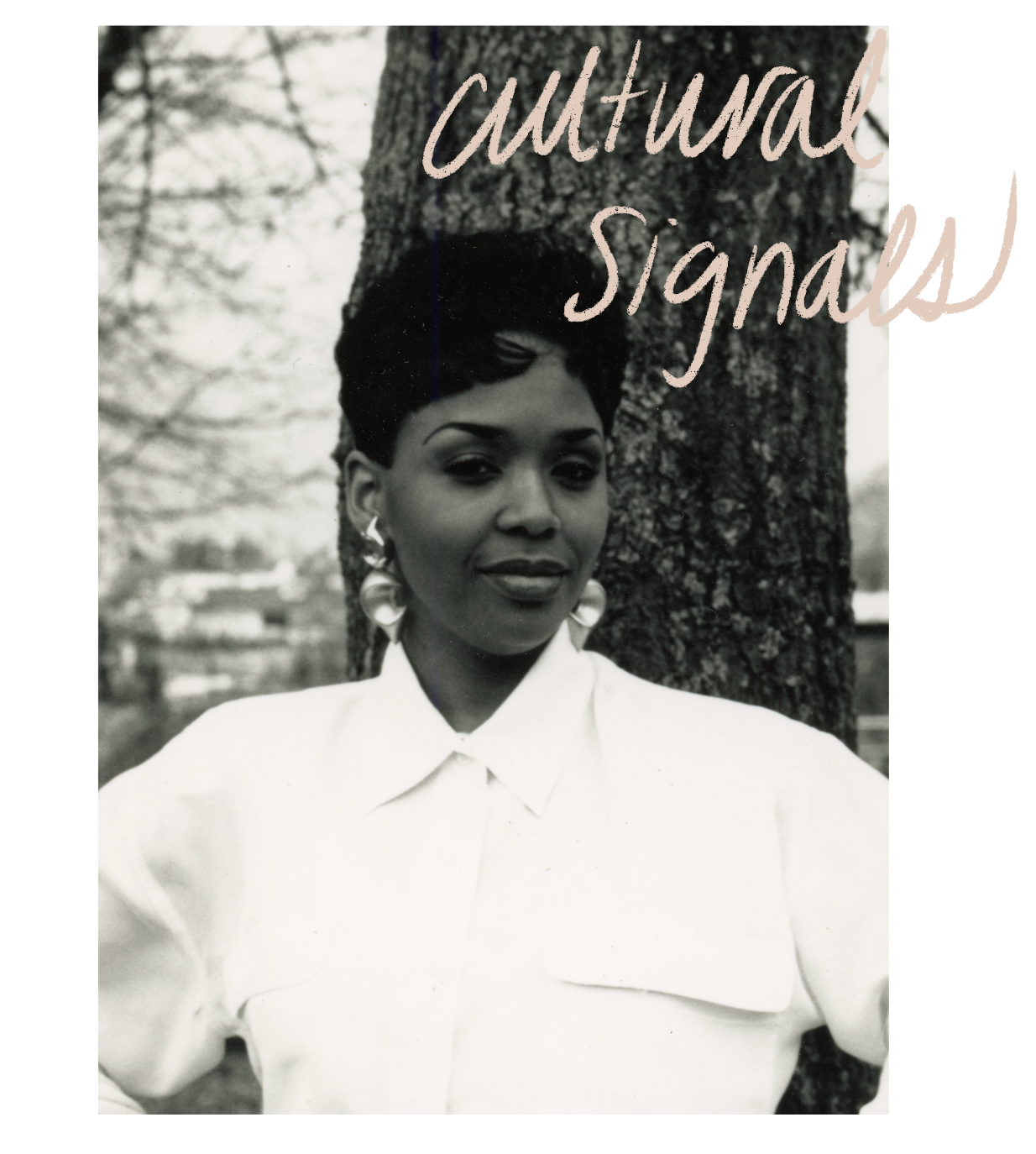

Black style has always held its own timeline both in sync and distinct from dominant culture. As style evolves it can tell time. Hairstyles, fashion, makeup, and accessories aren’t just aesthetic choices—they’re timekeepers. A set of bamboo earrings, a high-top fade or a stacked gold chain can locate a photo in a specific era of cultural memory. These details tell us where we were, what was considered beautiful, and how identity was shaped and expressed in that moment.

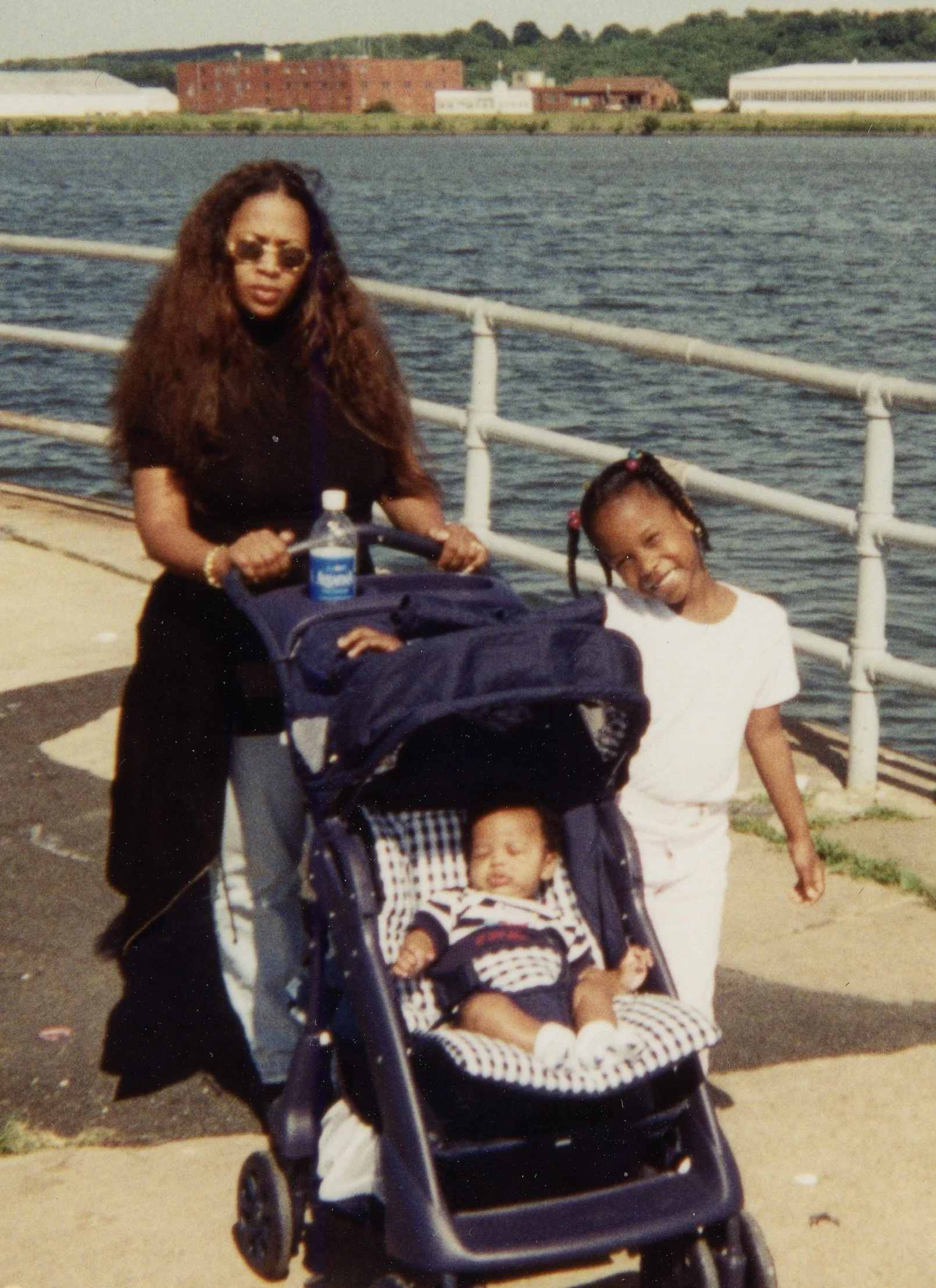

circa 1996

In my family’s archive, using my mother’s hairstyles became a point of reference. Her short, feathered haircuts appear in the early 90s. Then a short bob in the mid-90s during my toddler years. By the late 90s, her hair was down her back. I was able to identify the timeline of these images, without a date ever needing to be written.

circa 1999

These visual cues become essential when time isn’t explicitly stated. Style leaves behind a visual record – what we wore, how we wore it and the cultural atmosphere that shaped those choices. It becomes one more language for locating memory.

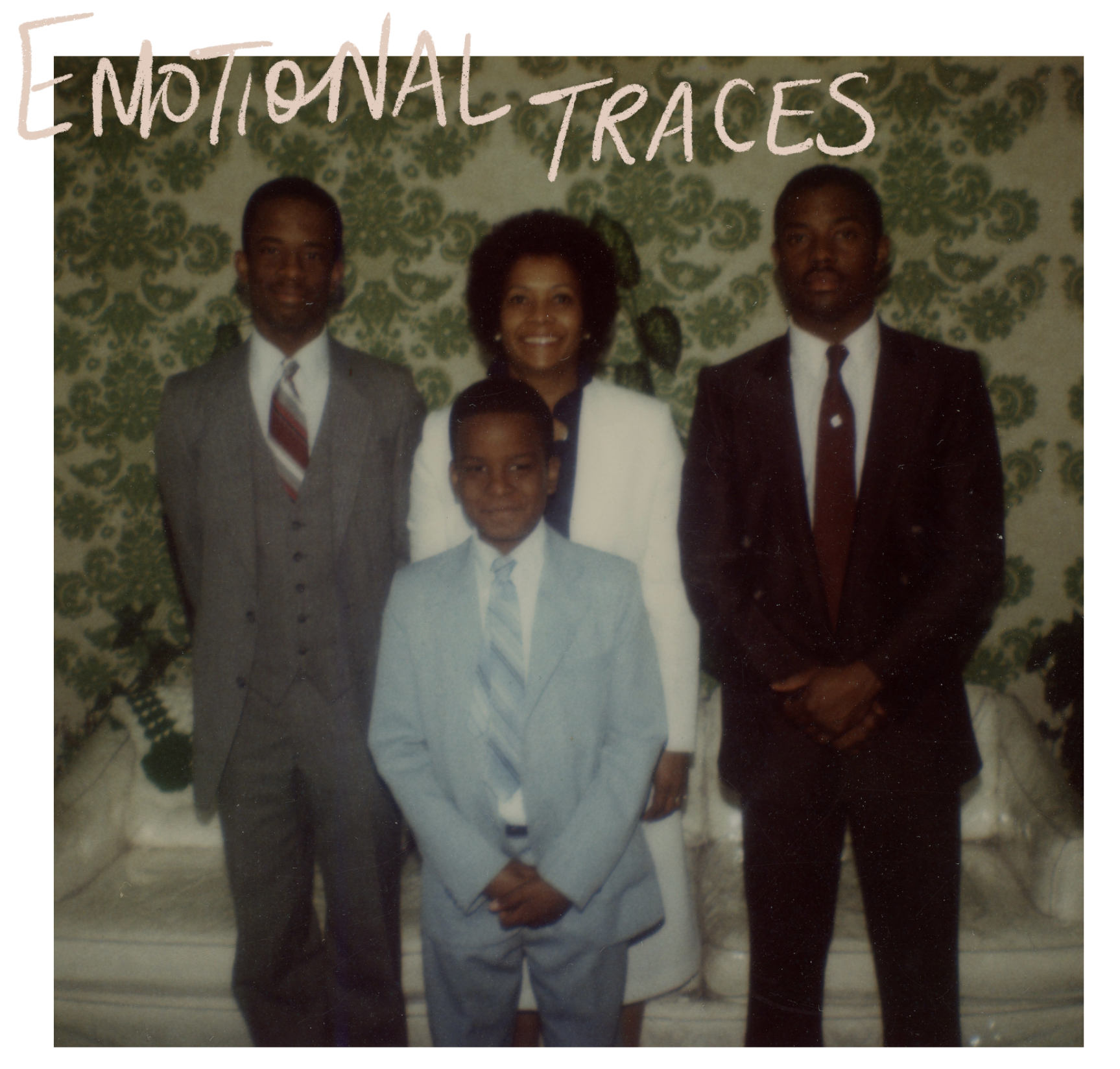

Emotional time can be marked by absence and ambiguity. Sometimes, it’s not about who’s in the photo, but who isn’t. You start to notice when someone disappears and absences can point to timelines just as much as appearances can. My grandmother passed away in 1983, so when she stopped appearing in family photos, I understood that we had crossed a threshold. A subtle but unmistakable clue, her absence in the family photographs became a silent timestamp.

One of the last photographs I collected left me deeply puzzled. It was a portrait of a man that looked exactly like my grandfather, only he was much older, almost elderly. The image had a browned and fading surface much like the photographs that I had dated to be taken in the early 1940s. Asking my family members who the man in the photo was, no one knew. My intuition told me he came before – possibly a generation or two back. I still don’t have the answer. Some moments resist clarity and sitting with the ambiguity becomes its own kind of knowing. These small signals, felt more than seen, are just as much a part of the timeline.

An unknown ancestor.

Tracing time through photographs isn’t just a technical process, it’s an art. It requires attunement to both the material and immaterial. You must read between the lines, lean on emotional memory, cultural context and visual instinct. It can be named outright or it can linger in a gesture, a hairstyle or a missing face. This way of seeing isn’t just part of how I approach the archive, it’s central to my artistic ethos. As the keeper of these photographs, I read them not only for what they show, but for what they reveal over time. Tracing time is how I stay in conversation with the past—how I honor what’s gone, cherish what remains, and make sense of the spaces in between.