The Shape of Departure

It wasn’t until I stepped into my grandfather’s house that it hit me — he may never come home again. His home in Maryland had been sitting empty for months. We had come to check on it. He’d been in and out of hospitals and rehab facilities for so long, and in his absence, the air inside had grown still. I moved through the space slowly, letting my eyes settle on familiar things: the green carpet, the aged wallpaper in the front sitting room, and the record player that hadn’t spun a new vinyl in years. Everything remained as it was but somehow changed. As if the house had been waiting, but no longer expecting.

It was the summer of 2024, and I had been preparing for my first group photography exhibition. My camera rarely left my side. That day, I felt an urgency to document — not just objects, but something harder to name. The atmosphere. The in-between. The feeling of things shifting. Later, I came across a series of essays by Solange Knowles in Document Journal about the passage of time and the importance of documenting through transition. Her words gave language to what I was already doing — witnessing something slip away in real time, and reaching for my camera in response.

The reality was, we were losing the anchor of the Preston family. And as I stood in that house, I began to remember everything it had carried and saw how much of him remained. The house held more than memories, it held history.

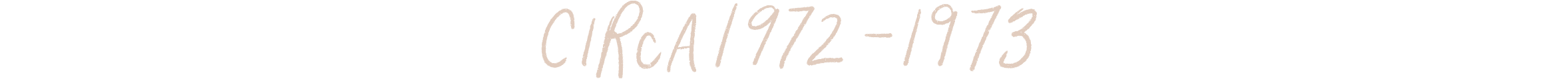

My grandparents moved into their home in 1972, shortly after their third child, my uncle Ed, was born. It’s where they raised their three sons and built a life for themselves. In the early days of integration, discriminatory housing practices in Silver Spring shaped where Black families could live. In the Tamarack Triangle, my grandparents—alongside other Black homebuyers—were steered to a single street, echoing the patterns of redlining. Yet within those constraints, a tight-knit community took root. As a child, I had always thought of my grandfather’s neighborhood as a Black one. I didn’t yet understand the limits that made it so.

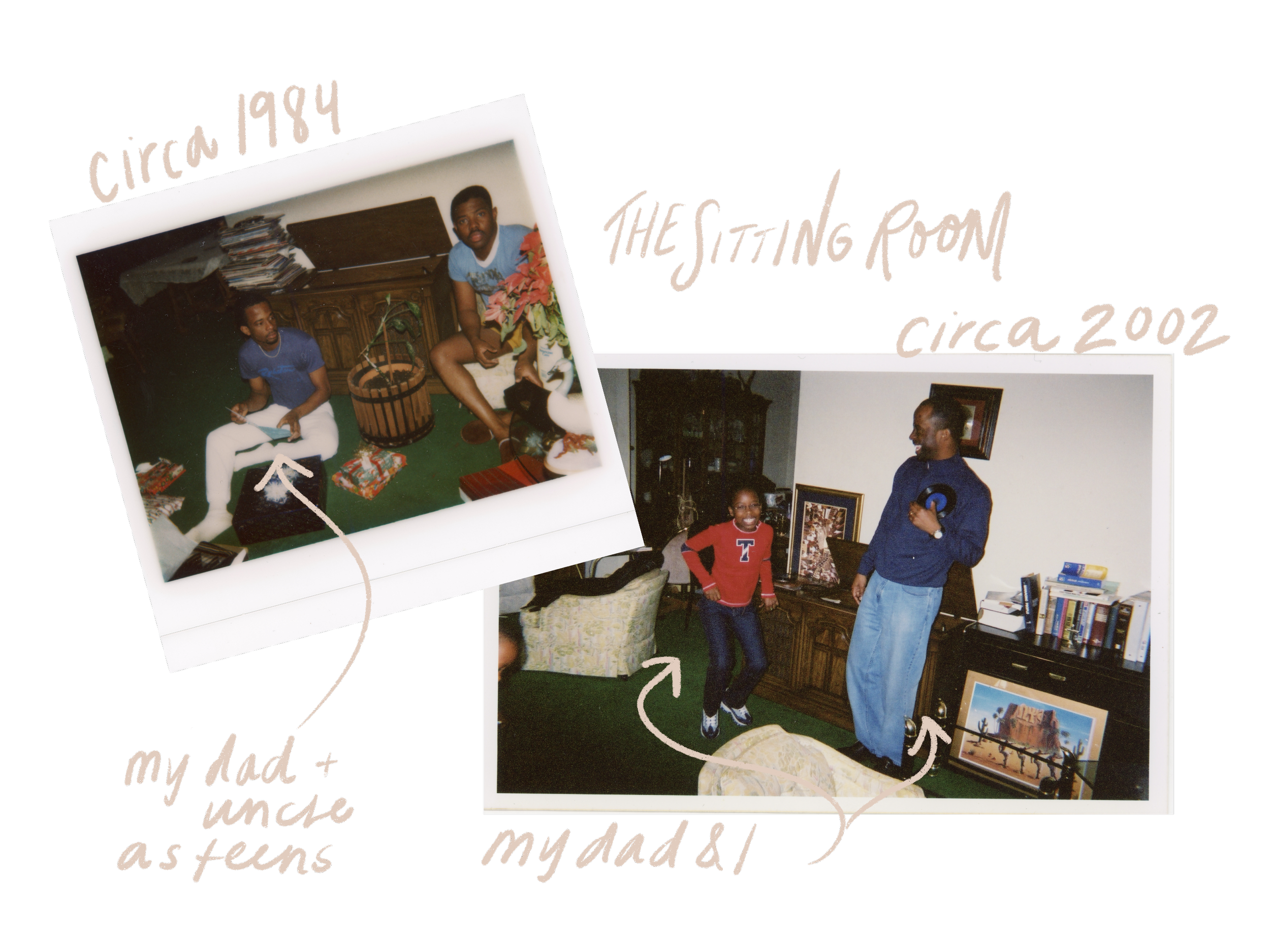

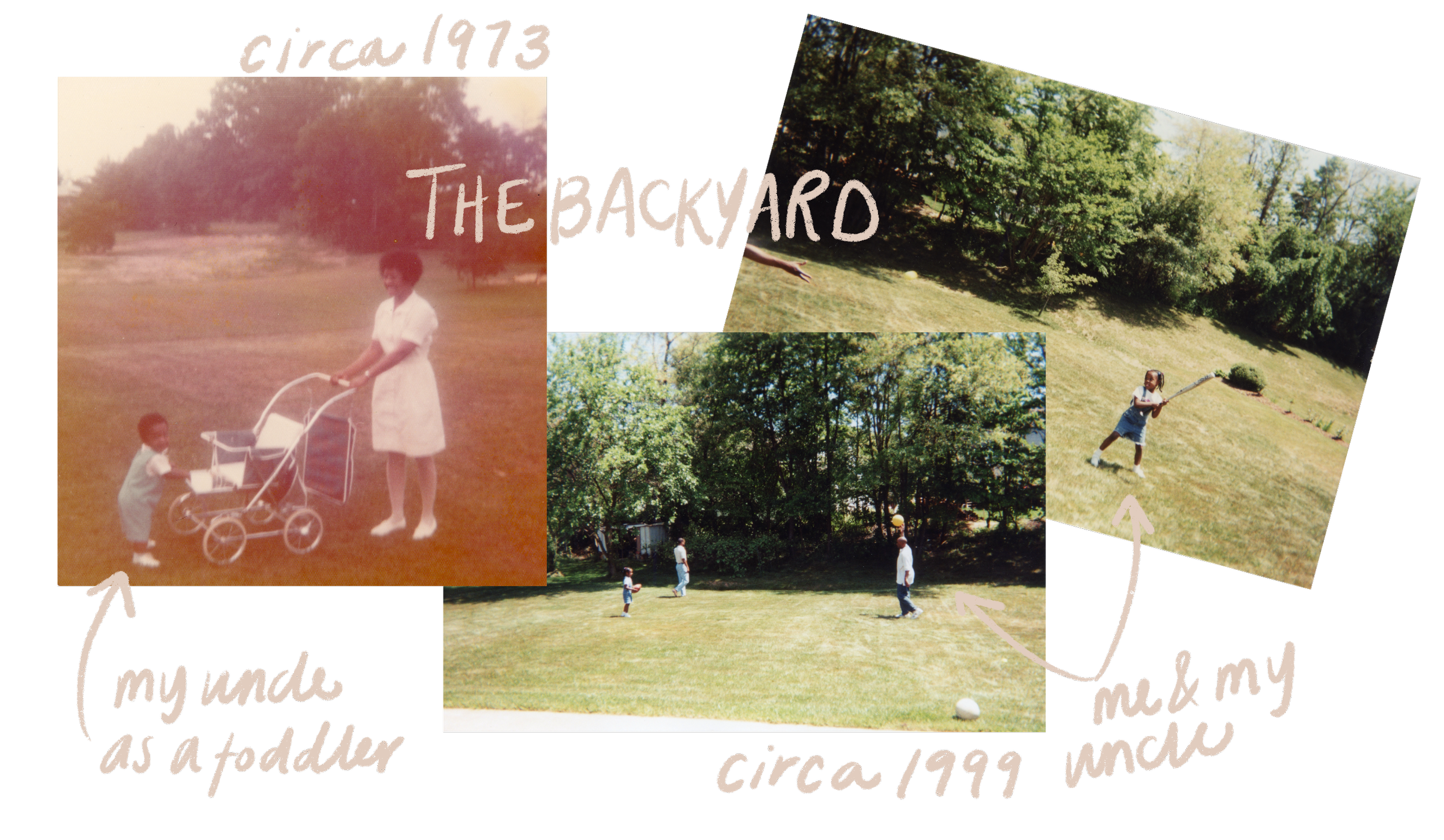

Still, there was no shortage of stories from my father and uncles growing up in the neighborhood, full of mischief and youthful time to waste. My own childhood memories live in the corners of that house: playing in the backyard, laying on the green carpet, flipping records in the sitting room. There was the wood paneling, the recliner where my grandfather sat to watch the news, and the table covered in framed photos of me, my brother, our cousins, my great-grandfather, and my grandmother I never got to meet.

And then there were the objects: Omega Psi Phi paraphernalia, North Carolina A&T memorabilia, Bibles, and framed certificates. My grandfather was a proud Omega man, an HBCU graduate, a deacon, and above all, a family man. Naturally, I turned my lens toward those details — capturing not just the objects, but the spirit they carried. Faith, legacy, pride, and love; all held quietly in the rooms he called home.

That summer, I didn’t just document the house — I documented him. One of those moments was his 90th birthday, spent in a hospital room surrounded by the people who loved him most – people shaped by his generosity, his presence, his care. It was a celebration, but it felt both tender and temporary as if holding joy and grief in one hand. We were in the midst of a period of passage, without knowing how close we stood to goodbye. Just three weeks later, he would make his final transition.

Final portrait of Eugene H. Preston Jr.

I didn’t know what these photographs would become, only that I needed to make them. That by facing the impending absence through my lens, I could stay present inside something too big to name. What I was witnessing was the shape of departure — not just of my grandfather, but of a time, a generation, a way of being. This is how I chose to hold it. What I made that summer weren’t just images, but offerings — to memory, to time, to the man who made so much possible.